Sovereign Seeds: Reclaiming MENA’s Agricultural Future

Reviving local food systems and unlocking rural prosperity

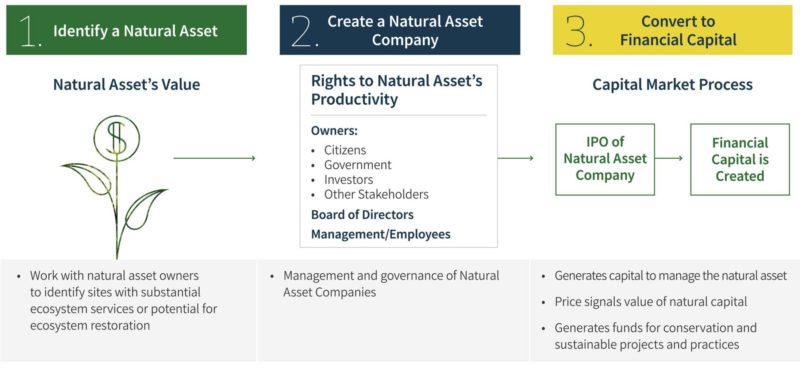

A new way to invest in our planet

Natural Asset Companies (NACs) are a potential game-changer on a global scale. NACs will be newly formed, sustainable enterprises that hold the rights to the productivity and health of natural assets like land or marine areas. They are a new asset class on the New York Stock Exchange enabling owners to convert nature’s value into financial capital, using that capital to re-invest in the natural assets to protect them or improve their sustainable use. In this way, we could see huge areas of biodiversity and agricultural land around the world saved and regenerated. Early signs suggest a great deal of interest from investors looking for impact at scale, and the timing, with ESG and COP26 front of mind, may be perfect.

Most of us love nature but perhaps it has taken the pandemic to help us realize just how much we have taken it for granted. We know that nature is under threat, but do we know the full extent of the problem?

Nature is declining around the world at an unprecedented rate as we exploit it more quickly than it can renew itself.

Nature is declining around the world at an unprecedented rate as we exploit it more quickly than it can renew itself. Ecosystems are estimated to have reduced by almost half, multiple species are likely to disappear, land degradation has reduced productivity, and millions of people are at greater risk from extreme events due to climate change.

Currently only about 15% of the world’s land and 7% of the oceans are protected. The High Ambition Coalition for Nature and People states that “there is growing scientific research that half of the planet must be kept in a natural state” and it has set an interim goal of achieving 30% protection by 2030.

However, the cost of protecting natural ecosystems is huge, with some estimates indicating that between $300BN and $400BN is needed each year to preserve and restore ecosystems. This compares to only around $52BN that is funding conservation projects at present.

But as the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) makes clear, “nature loss poses both risks and opportunities for business, now and in the future. More than half of the world’s economic output – US$44tn of economic value generation – is moderately or highly dependent on nature”. Globally, natural assets produce an estimated $125 trillion annually in ecosystem services, such as carbon sequestration, biodiversity, and clean water. As Mauricio Claver-Carone, President of IADB, says, “Unlocking the tremendous intrinsic value of nature will allow countries to leverage their natural capital for conservation and human development goals.”

Douglas Eger, businessman, entrepreneur, and conservationist is the Chair and CEO of Intrinsic Exchange Group (IEG), the company that works with natural asset owners to form and list the new asset class of NACs. The IEG has put forward a transformational solution that rejects the assumption that nature is only a cost, by creating investable assets that provide financial capital for sustainable production from those natural assets.

The IEG has put forward a transformational solution that rejects the assumption that nature is only a cost, by creating investable assets that provide financial capital for sustainable production from those natural assets.

Eger explained that he has felt close to nature since he was a child. As he grew older, he became increasingly frustrated with the speed, scale, and commitment of moves to protect our natural world. His interest in “natural capital” developed and his vision to include nature in the mainstream economy began to emerge.

Douglas Eger

Even if we don’t recognize it, natural assets have a huge value, so Eger asked himself, “could we value natural capital?” Land and water are very productive assets. So how could the flow of benefits from these natural assets be monetized, whilst using the capital raised to invest back in them to ensure they are protected and used sustainably? And, crucially, how do we do this at a scale so it makes a big and permanent difference?

In essence, he wanted to create an equity-type structure for these natural assets, building a long-term market of buyers and sellers to fund and trade them. The vision was clear, but many parts of the jigsaw needed to be developed. Not least, the right legal structures, accounting methods, and valuation. Then, investor interests in conservation would need to be aligned through a market solution with the scale and speed of the stock markets. The support of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) would be critical as it could provide the platform to trade.

Eger’s plan isn’t a pipedream — significant progress has already been made. IEG has now partnered with the NYSE to list and trade NACs on the exchange, receiving initial funding from IDB Lab, the IADB, The Rockefeller Foundation, and others.

NACs are granted the rights to the productive use of the natural resources in a defined area from the asset owners, similar to water or mineral rights. On public lands, natural asset owners are typically the local and national government entities, whereas on private lands the asset owners are likely to be farmers, ranchers, or forest owners. A NAC is primarily owned by the natural asset owner, investors, and other stakeholders. The owners grant the rights to the natural asset and ecosystem services of a particular area to the newly formed NAC.

When the NAC is floated on the NYSE, the proceeds from the IPO are used to protect and grow the natural assets and the ecosystem services they produce. For example, on agricultural land, the proceeds fund the conversion to regenerative practices.

“Our hope is that owning a natural asset company is going to be a way that an increasingly broad range of investors have the ability to invest in something that’s intrinsically valuable, but, up to this point, was really excluded from the financial markets,” NYSE COO Michael Blaugrund told Fortune recently.

One of the main aims in creating NACs is to transform the way investors value nature, aligning investor interests in conservation to give the solution scale and speed. Supportive government policy is key, but it can take many years to deliver outcomes; companies may want to pivot to sustainable practices, but long-term funds are often very limited; and philanthropy has a major role to play but often it is not collaborative or large enough to make a significant difference compared to the global capital flows of stock markets.

NACs can bring together investors looking for evidence-based impact with companies and Governments who want to deliver a more sustainable future. The issuer is the NAC and the investors in them could be asset owners, like pension funds, the sustainable funds of asset managers or family offices, development banks, sovereign wealth funds and retail. According to Douglas Eger, investor interest has already been very strong; they can see the opportunity for capital gain as well as evidence-based outcomes which align with their environmental priorities (as part of the increased focus on ESG and impact funds).

We have seen the harm that the current approach to nature can bring. The options that damage the land or water look financially more attractive and so that’s where resources go. What if that equation could be changed so that there is a greater reward for the good stewardship of those natural assets? Natural assets hold significant value and their value increases over time if they are not destroyed or made unproductive. NACs are a way to tap into that productivity, and use the capital raised to implement a sustainability plan that improves and protects them.

What if that equation could be changed so that there is a greater reward for the good stewardship of those natural assets?

Consider the enormous potential for areas of high biodiversity, especially in the less advantaged parts of the world: Coral reefs, African habitats, rainforests, agricultural lands shifting to a regenerative model, and highly degraded areas that can be restored and put back into productive use.

This is how it works:

https://www.intrinsicexchange.com/solution

First, there must be genuine interest from a significant number of investors when NACs are brought to market. The market needs to be proven with a few successful issues, so that the NACs become a valid sustainable or ESG investment choice. As mentioned above, the early signs are good. Indeed, according to Douglas Eger, “large companies are also taking notice and it is likely that a very significant multinational will make public its support in the very near future.”

Secondly, scale and speed are critical. To be successful, NACs need to increase in number and size, and be seen to offer the kind of evidence-based ESG investment at scale that is in much demand. The model needs to be proven on the ground with the NACs sustainability plan being delivered as intended, and with clear data to support that.

Thirdly, there are bound to be regulatory challenges in some countries or with some governments, if it’s considered that NACs bring political risk. Governments may be running a very different agenda, or there’s the risk of NACs being misunderstood due to their newness, relative complexity, or the skepticism arising from years of investment “greenwashing”. For example, there may be an assumption that this is just another way for those with influence or capital to make money from the natural rights of the public. Therefore, a robust link to the sustainability plan is so important as well as an understanding that the ownership of a public asset stays with the public. It is not the ownership being transferred but the right to the productive use of the natural resources.

Finally, for any innovation, and any market instrument, the timing for the issuer must be spot on. Given the uncertainties created by Covid globally, it is hard to predict anything on that front.

Not everyone believes NACs will be a solution to protect and sustain nature. Some are concerned that this could lead to the large-scale sell-off of our natural world, which will only benefit wealthy investors looking for a new source of profits wrapped up as ESG. According to Nature of Change, “the creation of NACs could lead to the privatization of the natural assets we all share”. Much will depend on how the rights to the “ecosystem services” are used.

As with other investments claiming to have a high environmental impact, NAC activities and claims will need to be tested independently to show that the funds raised are being used by the NAC to invest in sustainable practices, and that these practices are securing the environmental outcomes promised. It does look like robust governance and measurement is being put in place to give stakeholders more confidence that NACs will be run to protect the planet. Advisors like Bob Herz, former Chairman of the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), have helped IEG to develop the accounting framework needed to better value “ecosystem services”, so that “statements of ecological performance” can be produced for NAC investors. The audit firms could provide the assurance needed for investors, but so far it is hard to gauge exactly how the same assurance will be provided for the public, who own these common goods, and the local people most closely effected by the activities of the NACs.

To keep NACs true to their mission, impact management and measurement concepts “will also be codified in each NAC’s charter, bylaws and governance structure” says Eger.

Details are not yet available, as SEC approval for the NAC construct is still pending, but as Eger says, “formal oversight of ecosystem services valuations (“ESV”), ecological health indicators (biodiversity, etc.), and reporting are integral to the NAC accounting framework, exchange rules, and corporate governance. A NAC’s performance is based on the maintenance, restoration, and growth of ecosystem services produced by natural assets under its management”. Listing standards will need to be reviewed once they are available, as these will explain the requirements for how NACs must (or must not) operate. To keep NACs true to their mission, impact management and measurement concepts “will also be codified in each NAC’s charter, bylaws and governance structure” says Eger. Most importantly, “this legal/regulatory framework is intended to put an unambiguous focus on maximizing the production of ecosystem services and avoiding the potential to ‘change course’ in a way that would run contrary to the mission of NACs and the interests of its stakeholders (e.g., engaging in extractive industries)”.

It is still early days, but some governments have already acted on the huge potential for NACs. In Costa Rica, IEG is collaborating with the government to explore the creation of a NAC to value and finance conservation so that the country’s social priorities can be met. Costa Rica has ambitious national and global environmental commitments (such as the High Ambition Coalition 30 x 30 goal).

Andrea Meza Murillo, Minister of Environment and Energy, Costa Rica comments: “In Costa Rica, IEG is supporting us to build a pilot project for establishing a Natural Asset Company. This will deepen the economic analysis of giving nature its economic value, as well as to continue mobilizing financial flows to conservation. All of this, in a key moment when we have to meet the social and economic needs of our people and comply with what science tells us about the “30×30 Goal” — protecting at least 30 percent of land and oceans by 2030.”

Efforts to protect nature are not new, of course. Let’s hope existing conservation efforts work in coordination with the birth of the NACs, given their shared objectives. For example, the High Ambition Coalition (HAC) for Nature and People is an intergovernmental group of 70 countries (co-chaired by Costa Rica and France, and by the UK as Ocean co-chair) championing a global deal for nature and people with the central goal of protecting at least 30 percent of world’s land and ocean by 2030. The 30×30 target is a global target that aims to halt the accelerating loss of species and protect vital ecosystems that are the source of our economic security. Global Ocean Alliance “30 by 30” is a UK-led initiative. Its aim is to protect at least 30% of the global ocean.

The Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) was announced in July 2020 and aims to deliver a risk management and disclosure framework for organizations to report and act on nature-related risks, to support a shift in global financial flows toward nature-positive outcomes. These are just some of the examples, with many more represented at COP26. NACs could provide the practical, market-based instrument needed for these collaborative entities to deliver their high ambitions backed by investors and companies around the world. It remains to be seen whether NACs will fulfill their potential at sufficient scale, as well as stay true to their purpose of putting nature first, but there is hope from what we have seen so far. If NACs can provide an authentic investment in nature, and move beyond greenwashing, that’s a big step forward.

***

NACs are an ambitious innovation with plenty of heavyweight backing. They seem to offer a genuine way to scale up funding for nature’s protection and sustainable use. If any of the impact entrepreneurs reading this have ideas on protecting nature in other, innovative ways then let’s start a discussion!

Related Content

Deep Dives

Featuring

Clarisse Awamengwi

IE Correspondent

July 17 - 12:00 PM EST

Featuring

Russell McLeod

July 24 - 12:00 PM EST

RECENT

Editor's Picks

Webinars

News & Events

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates about new Magazine content and upcoming webinars, deep dives, and events.

Become a Premium Member to access the full library of webinars and deep dives, exclusive membership portal, member directory, message board, and curated live chats.

At Impact Entrepreneur, we champion fearless, independent journalism and education, spotlighting the inspiring changemakers building the Impact Economy. Diversity, equity, sustainability, and democracy face unprecedented threats from misinformation, powerful interests, and systemic inequities.

We believe a sustainable and equitable future is possible—but we can't achieve it without your help. Our independent voice depends entirely on support from changemakers like you.

Please step up today. Your donation—no matter the size—ensures we continue delivering impactful journalism and education that push boundaries and hold power accountable.

Join us in protecting what truly matters. It only takes a minute to make a real difference.

David, fabulous article. Thank you. I’m developing a green finance course for government officials and company executives in China and ASEAN. NACs will weigh heavily in the course. I’d like to write a case based on real NAC examples that not only highlight the promises and challenges but provide more detailed mechanics of NAC from formation to listing as well. Where would you recommend I start?