Sovereign Seeds: Reclaiming MENA’s Agricultural Future

Reviving local food systems and unlocking rural prosperity

A visionary designer reinvents the material economy

Image Courtesy of Christien Meindertsma

“What I’m a little bit annoyed about,” says multi-award-winning circular economy designer and artist Christien Meindertsma, “is when people call what I use ‘waste wool.’ In reality, I’m mostly working with virgin wool—a beautiful, noble material. The fact that we throw it away doesn’t make it waste, it’s just cultural stupidity”.

For two decades, Dutch designer Christien Meindertsma — whose work is featured in New York’s MoMA and London’s V&A — has been researching and creating sustainable products while exploring the stories behind product life cycles. Her mission is to help build — and rebuild — European fiber and virgin material markets.

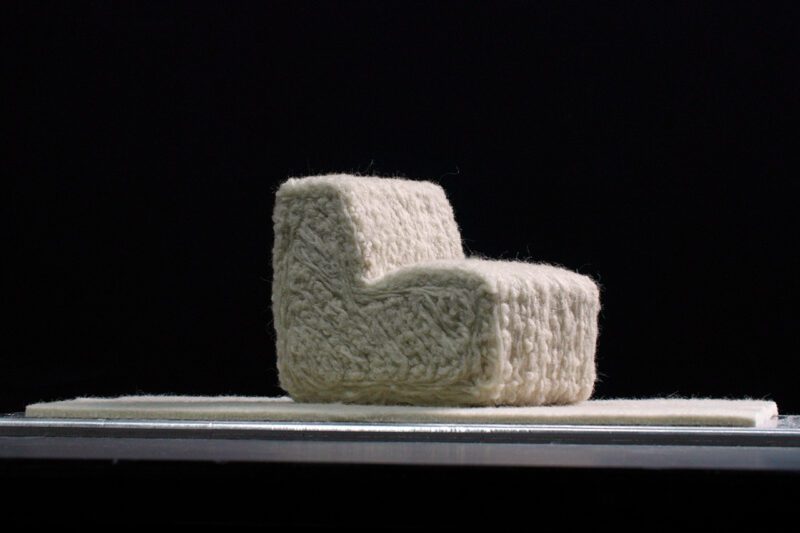

A graduate of the Eindhoven Design Academy in 2003, Meindertsma creates wool and flax furniture, tiles, and other products using locally sourced virgin materials from the Netherlands, entirely free of synthetic components. She also aims to pioneer the development of larger-scale sustainable products for diverse markets.

Christien Meindertsma in her Netherlands based studio. Image by Ines Vansteenkiste Muylle.

Her production processes — which include co-creating two robots — eliminate the use of glue and the large amounts of water typically required for similar products. Her goal is to make all her creations re-constructible and reusable.

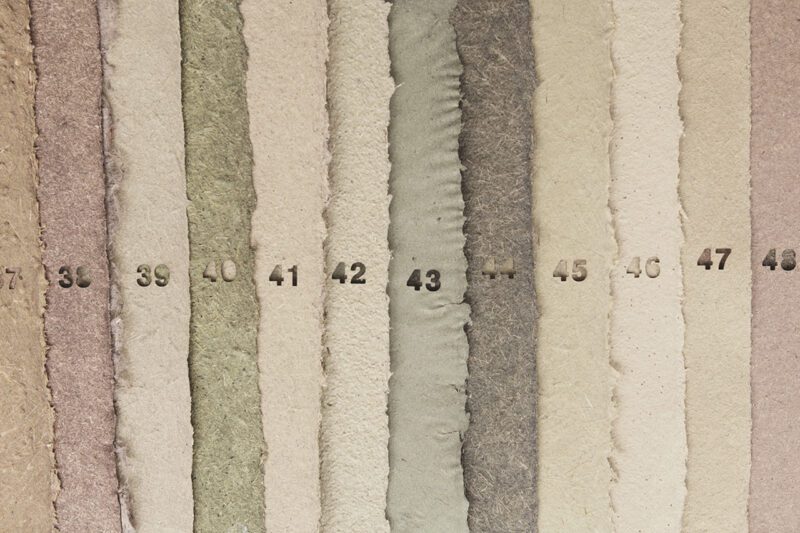

In her 2020 project, Fibre Market, she shredded woolen sweaters into small fibers, creating a yarn with colorful “flecks” made from the recycled wool.

She expresses dismay at the way industries prioritize profit over environmental responsibility: “Everybody seems to be pointing fingers at someone else. For example, the furniture industry isn’t addressing the issue because they believe it’s the foam rubber industry’s problem, and so on.”

She also finds it incredible that the Netherlands discards 1.5 million kilos of virgin wool every year while importing wool from Australia and New Zealand. She notes that the majority of local flax — “a wonderful fiber” used to make linen — is exported to China for further production.

“Our ancestors wore linen and wool — not cotton or polyester,” she explains. “I work with materials deeply connected to our land, history, and culture. There are so many layers of meaning and reasons to use them. It’s fascinating and inspiring.”

So why does so much wool come from the other side of the world? “In Europe, sheep flocks offer a variety of colors and textures,” she says. “There’s incredible richness in that, but the industry prefers wool that’s white and uniform.”

“Australian wool is merino, so finer,” she continues. “New Zealand wool isn’t always finer, but it’s more uniform in quality and it’s white. That’s why the Netherlands imports wool from those countries — it’s more predictable and acceptable for the industry.”

Wool Chair. Image Courtesy of Christien Meindertsma

Meindertsma’s efforts to showcase how natural materials are used in everyday products—and to expose the unsustainable processes involved — have not gone unnoticed.

Her production processes — which include co-creating two robots — eliminate the use of glue and the large amounts of water typically required for similar products.

In 2009, her book Pig 05049, named after a real pig, documented the many consumer products (including photo paper and biodiesel) derived from that single animal. The book earned her the prestigious Danish design prize, the Index Award, giving her €100,000.

She used the prize money (after taxes) to create another award-winning innovation: the Flax Chair. “With that money, I bought the harvest of a flax field from a farmer in Holland to see if I could process it industrially and locally,” she explains.

49 Prarie Plants. Image Courtesy of Christien Meindertsma

“Currently, 90% of Dutch flax is exported to China for production. It’s a shame because we once had a flourishing flax and linen industry here. Some of it remains, but not much.”

Several years and numerous flax-based products later, the Flax Chair — a full-sized chair made entirely from flax and bioplastic — won the Dutch Design Award and Future Award.

Christien and the newly invented Wobot – a robot which makes zero waste, pure wool sofas.

Most recently, she returned from the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) in Melbourne as this year’s winner of the MECCA x NGV Commission series, a social change initiative designed to elevate women in art and design.

The series annually recognizes one woman designer or architect and provides financial support to develop new ideas. The funding enabled Meindertsma to design a new iteration of her ‘wobot,’ a robotic machine capable of creating 3D woolen forms of unlimited size.

With the earlier version of the machine, she created and sold 250 woolen sofas made entirely of wool. Now, she aims for the latest version to produce even larger items, such as walls, acoustic panels, and 3D-formed insulation for cars, boats, and planes. Her goal is to refine the process to bring these products to furniture markets more quickly.

Wool Chair. Image Courtesy of Christien Meindertsma

Meindertsma has worked hard to invest in herself, but she has received little external financial support. Finding funding for experimentation and research, she says, is a significant challenge.

Still, she acknowledges that the Netherlands has a “reasonably good” funding system for designers and artists. “Twenty years ago, when I was starting out, I applied for and received a stipend from the Dutch government cultural fund — €16,000 at the time (about €25,000 today),” she recalls.

She also credits the Dutch company Tools for Technology for co-investing with her in research and development, designing and creating machinery and equipment that helped bring her Wobot to life.

“Investors focus on business models and profitability; they want data. But there’s no data available for something that doesn’t exist yet,” she explains.

“What I’m looking for from investors,” she explains, “is funding to bridge the gap between working prototypes and actual product prototypes.”

“We have a machine that works well for wool, and we know it can print something very large and very strong. But to convince the furniture or building industries that this material is a viable substitute, we need to develop even more advanced prototypes,” she says.

Meindertsma is seeking test assignments to fund the creation of these prototypes and to support further experimentation. “We know mostly what we want to do, but there’s still some experimentation needed, and we can’t predict exactly how long it will take to reach the final result. That’s a challenge, because the industries we work with — and potential investors — are looking for certainty.”

Meindertsma admits that she and investors struggle to understand each other’s worlds. “Investors focus on business models and profitability; they want data. But there’s no data available for something that doesn’t exist yet,” she explains.

I need space to experiment, but I think many people see experimentation as something scary, something to avoid. In reality, experimentation is exactly what this world needs.

Despite the challenges, she remains optimistic about her work. “I have strong hope that it will work out,” she says, adding: “I just hope that in 50 or 100 years, people will look back and say: ‘Wow, they were really plastic-loving idiots, weren’t they? How bizarre that they polluted the Alps and even their own bloodstreams with microplastics, while throwing away good-quality natural materials at the same time.’”

Related Content

Comments

Deep Dives

Featuring

Clarisse Awamengwi

IE Correspondent

July 17 - 12:00 PM EST

Featuring

Russell McLeod

July 24 - 12:00 PM EST

RECENT

Editor's Picks

Webinars

News & Events

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates about new Magazine content and upcoming webinars, deep dives, and events.

Become a Premium Member to access the full library of webinars and deep dives, exclusive membership portal, member directory, message board, and curated live chats.

At Impact Entrepreneur, we champion fearless, independent journalism and education, spotlighting the inspiring changemakers building the Impact Economy. Diversity, equity, sustainability, and democracy face unprecedented threats from misinformation, powerful interests, and systemic inequities.

We believe a sustainable and equitable future is possible—but we can't achieve it without your help. Our independent voice depends entirely on support from changemakers like you.

Please step up today. Your donation—no matter the size—ensures we continue delivering impactful journalism and education that push boundaries and hold power accountable.

Join us in protecting what truly matters. It only takes a minute to make a real difference.

0 Comments