Sovereign Seeds: Reclaiming MENA’s Agricultural Future

Reviving local food systems and unlocking rural prosperity

Sandra Braga, Quilombola farmer on her land in Brazil that produces Marmalade of Santa Luzia.

If you find yourself in the Brazilian capital of Brasilia, in search of the world-renowned Marmalade of Santa Luzia, made by the Braga family, you’ll need to drive about 45 minutes south of the city and down a dirt road in Mesquita, Brazil. On one side you will see the lush and very biodiverse farm where the ingredients have been grown and the marmalade made by hand based on the original recipe handed down through generations of the Braga family since the early 1700s.

On that farm, owned now by Sandra Braga, there are many dozens of different plant and tree species growing in some of the deepest and healthiest soils in all of Brazil. The lush forest produces an incredible array of coffee beans, fruits, and nuts, while the rich soil in her fields — cultivated over the 300 years that her family has lived here — produces sugar cane, corn, melons, and manioc. Her land teems with life, from pollinators like bees and birds to many other animals that are all part of a healthy, thriving ecosystem.

If you look across the dirt road from Sandra’s farm, you’ll see hundreds of hectares of rows of industrial soy being grown. The soil under the industrial soy operation is so denuded they need to pump it full of fossil fuel-based fertilizers and pesticides. When the soil is completely used up, the land will be sold to developers, fueling the spread of the suburbs of Brasilia. Part of this industrial farmland was once part of the Braga family’s property, until it was stolen by intimidation forcing the family off their own land.

This cycle of violence, intimidation, and economic pressure is being repeated globally by big corporate farming interests against the world’s two billion smallholder farmers. Research has shown that 90% of tropical deforestation is happening because of this rapid expansion of industrial agriculture. 80% of the world’s food is produced by these family-owned small farms.

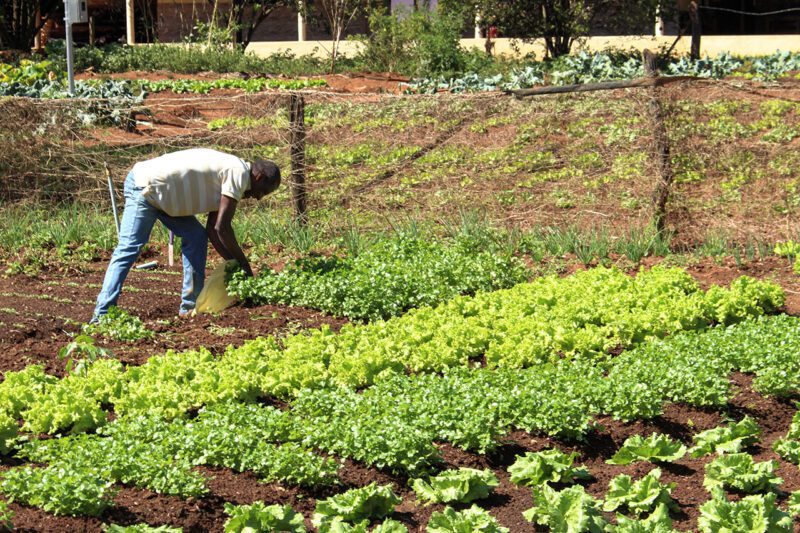

Quilombola farmers in Brazil use traditional farming techniques that maintain healthy soils.

The ecological, climate, and societal impacts of the current system are devastating and must be stopped, and just addressing one of these issues alone is not enough. If we are to meet any of the goals that have been set for climate, poverty alleviation, biodiversity, fair trade, and many more within the next 5-10 years, an integrated regenerative-for-all approach is needed.

Sandra Braga’s ancestors, the Quilombola founders of the Mesquita community, first settled on their farmland in the Brazilian Amazon in 1775. Almost 250 years later, Sandra still lives and farms on her family’s land – growing coffee, tangerines, sugar cane, corn, papayas, melons, and quince using the same farming techniques that were passed down generation to generation – although a lot has changed.

For starters, the family’s farm is smaller: Over the years, much of their land was stolen – including 283 hectares in 2000. These illegal land grabs have reduced their land to about 30 hectares. In tandem, like all farmers around the planet, Sandra has been forced to navigate and cope with the resounding consequences of climate change: new temperature variables, extreme storms and dangerous weather conditions, and increased risk of wildfires that further endanger crops.

80% of the world’s food is produced by these family-owned small farms.

The planet’s two billion smallholder farmers are at heightened risk: Among the globe’s most vulnerable communities, many smallholder farmers are already under near-constant threat of being pushed off their lands by developers. They rely on income from their crops, but with changing environmental conditions and risks, harvests are not always dependable – and can be critically impacted as a result of climate catastrophes. Additional financial blows to smallholder farmers’ annual income can further exacerbate the grave risk they face of being pushed off their land by industrial farming operations and developers.

This chart was created by the author based on the ECAM farmer study of Quilombola farmers that ReSeed currently works with.

These communities typically do not have access to financial credit services or agricultural technical support, and lack access to education systems, clean drinking water, and healthcare services. A recently published survey of Quilombola farming families in the Amazonian State of Amapa, Brazil, found that 93% had a household income of less than $15 USD per day and 70% less than $6 USD per day. 7 out of 10 Quilombola farmers had no education past primary school and 74% had no access to financial credit services. The World Bank and FAO have found even deeper levels of poverty among smallholder farmer households globally, earning on average $2 USD per day.

Many large-scale efforts over the years, from philanthropy to government aid, have been attempted to help stabilize family farmers on their land and encourage climate-friendly farming practices such as regenerative agriculture. All have failed to slow down the loss of smallholder farms and improve the livelihood of these families. Market-based solutions through supply chains and even climate finance programs like carbon credits have not worked either because these schemes have been too difficult and expensive for farmers to engage. Less than 1% of all carbon credits offered on the market prior to 2023 were sourced from any form of agriculture.

Until now.

In 2022, Sandra – and thousands of other farmers in Quilombola communities throughout Brazil – began harvesting a new crop from their land through a business partnership with an emerging climate finance company, ReSeed. Their new crop is data. Farmers work with ReSeed’s community-based agricultural technical partners to use an app to identify all of the plants on the farmers’ land, basic information about soil amendments and some socio-economic demographic data about the household and farm. ReSeed then uses cutting-edge, cloud-based, AI systems to analyze all of the farmer data to come up with very high resolution measurements of ecosystem services, such as carbon stored in the plants and soil on the land, water retention and quality, forest and vegetation integrity monitoring, to name a few. The raw data products are then turned into products like nature-based social impact carbon credits, deforestation-free certification and socio-economic certifications documenting poverty reduction, food system security, and supply chain integrity.

Brands around the world, including chocolatier Dengo, can purchase credits and certifications created from data from farmers like Sandra as a means to garner supply chain resilience and transparency, as well as increased climate and social impact. Farmers benefit directly as business partners in the transactions and are financially incentivized to increase the activities that promote climate resilience (storing, protecting, and drawing down more carbon), biodiversity, reversing poverty cycles, food chain security, and so much more.

Prior to ReSeed’s work with Quilombola farmers, 93% of families earned less than $15/day.

This financial model puts farmers at the center, monetizing their immense global impact to bolster their future work: 80% of carbon credit sales with ReSeed go directly to farmers and farmer support services – in many cases more than doubling annual incomes. Over a 12-month period, Sandra’s farm stored 5,993 tons of CO2 equivalents (each ton, a carbon credit) from soil and vegetation, the sale of which has led to a near 100% increase in annual household income in her first year of partnership with ReSeed. As a result, she has been able to increase the financial viability of her farm and do what she wants most: ensure that it can be passed down to future generations.

ReSeed uses a combination of highly advanced technology, working with partners like Google and many others to ensure that all data in the system is fully transparent and auditable by customers and farmers alike. Farmers are paid quickly in their local currency after their data products are sold. Ongoing agricultural, technical, and planning services for the farmers are paid for by ReSeed, so that farmers have access to regional regenerative farming strategies that will best increase the ecosystem, climate and community impacts that can be measured and verified.

Sandra and her mother Elpidia Braga, whose family has farmed their land for over almost 300 years.

Smallholder farmers are leaders in the fight against climate change. Due to the ecosystem services they provide, farmers must be regarded as leading business partners for anyone buying credits on the carbon markets. To draw down the needed gigatons of carbon in the atmosphere, 60 million hectares of regenerative farmland are needed. This is currently possible by partnering with the global south’s 600 million smallholder farmers who, on average, have three hectares of farmland each.

This solution for climate financing comes via creating a positive feedback loop between recognizing smallholder farmers’ ecosystem services – including climate and biodiversity – and then working with them to access climate and biodiversity markets. This model equitably compensates farmers for their ecosystem services, incentivizes their continued work for the future, helps to ensure their ability to retain their land, and can even allow for the improvement of their crops.

Partnering directly with the billions of people around the world who are engaged in smallholder farming ensures that climate finance projects are rooted in real-world benefits, fostering a sustainable and inclusive approach to combating climate change, and improving the livelihoods of those who are doing the most work to safeguard the future. At the very least, it ensures that future generations of the Braga family will be able to make their famous (and delicious) Marmalade of Santa Luzia.

Related Content

Comments

Deep Dives

Featuring

Clarisse Awamengwi

IE Correspondent

July 17 - 12:00 PM EST

Featuring

Russell McLeod

July 24 - 12:00 PM EST

RECENT

Editor's Picks

Webinars

News & Events

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates about new Magazine content and upcoming webinars, deep dives, and events.

Become a Premium Member to access the full library of webinars and deep dives, exclusive membership portal, member directory, message board, and curated live chats.

At Impact Entrepreneur, we champion fearless, independent journalism and education, spotlighting the inspiring changemakers building the Impact Economy. Diversity, equity, sustainability, and democracy face unprecedented threats from misinformation, powerful interests, and systemic inequities.

We believe a sustainable and equitable future is possible—but we can't achieve it without your help. Our independent voice depends entirely on support from changemakers like you.

Please step up today. Your donation—no matter the size—ensures we continue delivering impactful journalism and education that push boundaries and hold power accountable.

Join us in protecting what truly matters. It only takes a minute to make a real difference.

0 Comments