Sovereign Seeds: Reclaiming MENA’s Agricultural Future

Reviving local food systems and unlocking rural prosperity

Building back better for collective wellbeing

Credit: Isabelle Swiderski

A few years ago, in a moment of intense loneliness, Charles Montgomery grappled with how he could make his life in the city more connected and joyful. So he joined a group of people who were exploring the idea of self-funding a co-housing, urban village project in Vancouver: 25 households, all in one building, sharing a large kitchen, children’s room, dining area, shared garden, and shared workshop.

Charles happens to be the author of the book Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design, and the founder of the consultancy of the same name. He is deeply familiar with the challenges that come with designing urban spaces that are inclusive, safe, resistant to shocks, and conducive to wellbeing. And yet, there he was, struggling to pinpoint how to feel happier in his city.

According to the World Bank, about 4.2 billion people, or 55.3 percent of the world’s population, are located in cities today. This number is estimated to increase to more than six billion by 2045, and by 2050, 7 in 10 people worldwide will be living in urban areas.

New York City’s Vision 2020 initiative, a year-long, participatory planning process, opened up new stretches of the waterfront and access to waterways for transportation, housing, recreation and natural habitats. Credit: Isabelle Swiderski

We know cities are key economic drivers, often even outperforming their own countries in terms of growth. We also know that urbanization comes at a cost, particularly around transportation, affordable housing, and pollution but also around safety and access to public and green spaces. These issues are multifaceted and daunting and yet COVID-19’s biggest lesson might be that, triggered by crisis, transformational change can happen quickly. And in that move for change, big government can act as an accelerant if its policies are designed to optimize citizens’ wellbeing.

For our purposes, we might define wellbeing as how people are feeling and functioning in their everyday lives. Given all the dimensions this encompasses when societies are largely dependent on our ability to live together, should a post-pandemic “Build Back Better” movement start with asking how we might (re)build better cities? Because human wellbeing, cities, and environmental sustainability are now, more than ever, inextricably linked.

By 2050, 7 in 10 people worldwide will be living in urban areas.

As Charles explains, this understanding is starting to emerge: “The remarkable thing is that many of the things we do just to make a city happier, just to make people’s lives easier and more connected — these things also represent climate action. For example, allowing more middle density, in-fill housing in some traditional neighborhoods: this is a GHG reduction action. And yet it’s also an action for equity, allowing more people to live closer to shops and services and transit. It’s also a move for personal health, allowing more people to walk and bike in their neighborhoods, rather than spending hours in a car every day.”

Achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) will require deep commitment and coordination between local and regional governments to tackle challenges in energy and transportation, to address poverty, as well as inequalities in access to public services. Yet with these challenges comes opportunity to reimagine how the design of cities can unite all stakeholders in realizing that achieving wellbeing goals can lead to achieving other goals. People, planet, and profit can indeed cohabitate.

New York City, for example, notorious for its enthusiasm for the “highest and best use of land” and for harnessing urban planning’s ability to segregate and exclude, was the first city to explicitly tie the SDGs to its own long-term sustainability plan, OneNYC.

Should a post-pandemic “Build Back Better” movement start with asking how we might (re)build better cities?

Adriana Valdez-Young is an urbanist, a mixed methods researcher, a mother, and faculty member at the School of Visual Arts (SVA) and Parsons School of Design. She is based in New York City and has long been studying urban centers from the perspective of the people who inhabit them.

“I think we have to shift to a fundamental belief that everyone who lives in New York City deserves a place to live that’s not going to threaten their lives. This isn’t performative urbanism. People actually live here and are building their lives here. So until we fix that then we can’t design anything fair. And until we have the right people in the room, making decisions and with agency, with having a voice, then what we design is always going to be broken.”

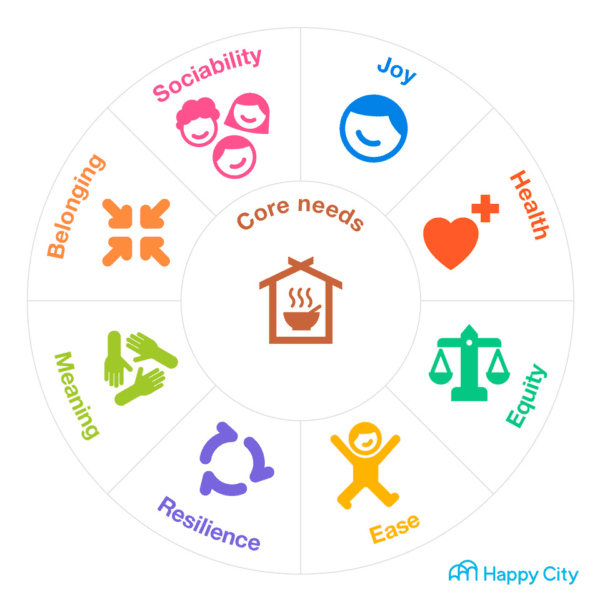

They have defined an urban happiness wheel connecting 9 key elements of psychological wellbeing, happiness, and life satisfaction.

Charles and the Happy City team have embraced this fundamental belief. Through evidence-based design experimentation and deep engagement of people who live in communities, they have defined an urban happiness wheel connecting 9 key elements of psychological wellbeing, happiness, and life satisfaction: core needs (food, shelter, security), social ties, health, wealth & equity, meaning & belonging, mastery, freedom, joy vs. pain, and sustainability.

The Happy City

This isn’t the first time we have tried to identify proxies to measure human happiness. GDP ties the size of the economy with individuals’ ability to consume, under the assumption that this will increase their happiness. The Gross National Happiness Index, first coined in the 1970s (though by whom is still in dispute), encourages equal consideration between economic and non-economic aspects of life. Kate Raworth’s and Janine Benyus’s collaborative effort, the City Portraits methodology, combines two domains (social and ecological), and two scales (local and global), to assess cities’ performance as stewards of people and planet.

We know the SDGs also provide a universal framework from which to gauge progress, but measurement in determining wellbeing is deeply connected to consultation and, ideally, co-creation processes. These can be hindered by any number of obstacles: power structures and hierarchy, lack of common terminology, biases, time, space and resources, as well as the subjective and fuzzy perception that humans have of their own happiness.

Through their respective human-centered work with various clients and partners, both Charles and Adriana realize that, as messy and imperfect as any collaborative process can be, the experts on quality of life, inclusion, joy and resilience, in cities, are residents themselves.

Maybe the true role of an urban planner is to act as a catalyst, a translator of sorts, helping to turn visions into shared spaces, wishes and words into policies, so that cities of the future can fulfill their potential of delivering health, prosperity, and freedom for all the people who live in them.

A construction worker finds a spot to rest in Manhattan. Credit: Isabelle Swiderski

Frameworks are useful but can only serve to guide the work of listening and empowering communities to name and prioritize their needs. And whilst finding indicators that adequately measure the richness and complexity of human experience will no doubt continue to demand iterations, on the topic of designing more inclusive and participatory design processes, there is clear consensus.

As urban planning — and its practitioners and collaborators — reckon with the outsized impact they have on the happiness of an ever-increasing number of people, where will their priorities lie?

Adriana is optimistic: “It took this pandemic for us to just stop and listen and really take stock of problems that are seemingly intractable. We can solve them; we can make big changes. But we have to do it at a human scale. When we have these sweeping initiatives, we miss nuances and leave voices out. We have the technology to share, from community to community, what people are coming up with. We need to harness that.”

And indeed, as Charles and the other families went through the process of creating their urban village, they realized they needed to start with [talking about] values:

“Our [co-living] community is able to live our values by exposing ourselves to each other’s needs, by committing to the common good, by seeing the best in one another. It’s much easier to do when you work in smaller social groups, but I think we can build those systems in all of our neighborhoods, and throughout our cities, and in all our ways of working.”

To foster collective wellbeing, we must accept this gift of interconnectedness, this responsibility to each other and to our planet, and choose to nurture what we value beyond our own lives, as communities and societies. There are no shortcuts to happiness.

Related Content

Comments

Deep Dives

Featuring

Clarisse Awamengwi

IE Correspondent

July 17 - 12:00 PM EST

Featuring

Russell McLeod

July 24 - 12:00 PM EST

RECENT

Editor's Picks

Webinars

News & Events

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates about new Magazine content and upcoming webinars, deep dives, and events.

Become a Premium Member to access the full library of webinars and deep dives, exclusive membership portal, member directory, message board, and curated live chats.

At Impact Entrepreneur, we champion fearless, independent journalism and education, spotlighting the inspiring changemakers building the Impact Economy. Diversity, equity, sustainability, and democracy face unprecedented threats from misinformation, powerful interests, and systemic inequities.

We believe a sustainable and equitable future is possible—but we can't achieve it without your help. Our independent voice depends entirely on support from changemakers like you.

Please step up today. Your donation—no matter the size—ensures we continue delivering impactful journalism and education that push boundaries and hold power accountable.

Join us in protecting what truly matters. It only takes a minute to make a real difference.

0 Comments